Aspirin - Time For A Rethink?

Aspirin has been a cornerstone in preventing and treating heart attacks for over 100 years.

Its reign might soon be ending, though.

And for some people, it might be causing more harm than good.

As always, the devil is in the detail.

Growing up, it seemed like almost every adult took a daily ‘baby aspirin’ because it was ‘good for your heart’.

In clinical practice, it wasn’t that long ago that you added aspirin to a patient’s medication list if there was even a hint of cardiovascular risk.

We are learning from recent trials that we need to think far more carefully before prescribing aspirin.

But let’s be clear who we are talking about.

The use of aspirin in those who have had a heart attack, stent, or bypass surgery is typically referred to as secondary prevention.

For this group of patients, the benefits of antiplatelet therapy, including aspirin, are clear. You need to continue taking this medication unless your doctor explicitly tells you otherwise.

Where some of the controversy lies is in the setting of primary prevention.

Primary prevention refers to using a treatment to prevent a first event or the development of heart disease in the first place.

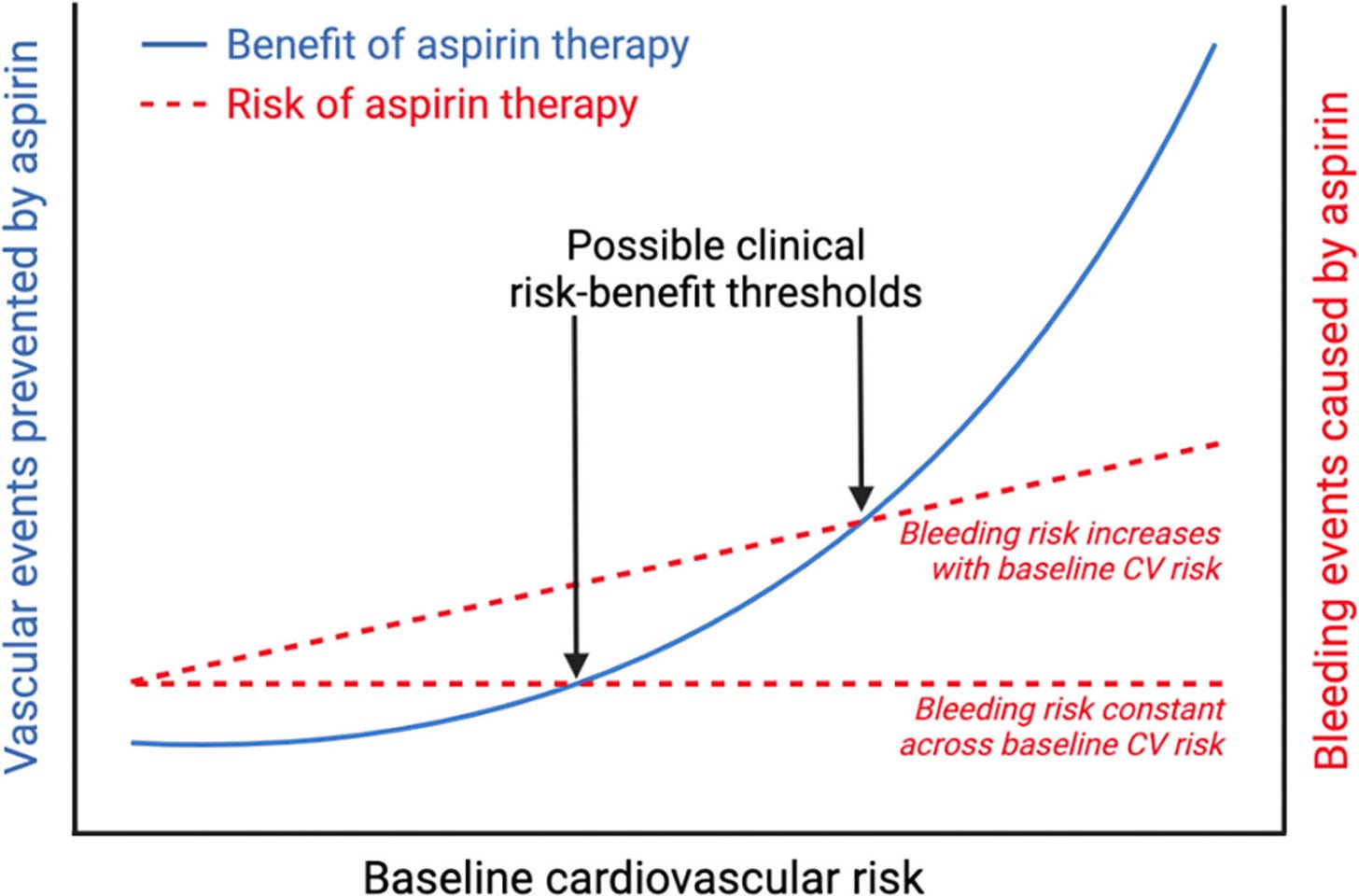

The risk of a subsequent heart attack is high for the person who has already had a heart attack and, by extension, are more likely to benefit from aspirin therapy.

However, aspirin therapy can also cause bleeding. And sometimes, very serious bleeding1.

When prescribing aspirin therapy, we must always weigh the risk of an event such as a heart attack against the risk of bleeding.

And everyone’s risk is different.

Initial studies of aspirin did show some benefit in the primary prevention setting, i.e. in those who had never had a heart attack previously. The benefits were modest, however, with aggregate risk reductions of 12 to 14%.

But these benefits often came at the expense of significantly higher rates of bleeding2.

To answer this question more definitively, several randomised trials were conducted evaluating the utility of aspirin therapy in the primary prevention of cardiovascular events and mortality in those:

Although there were some signals of benefit for cardiovascular risk reduction, the risks of major bleeding were obvious.

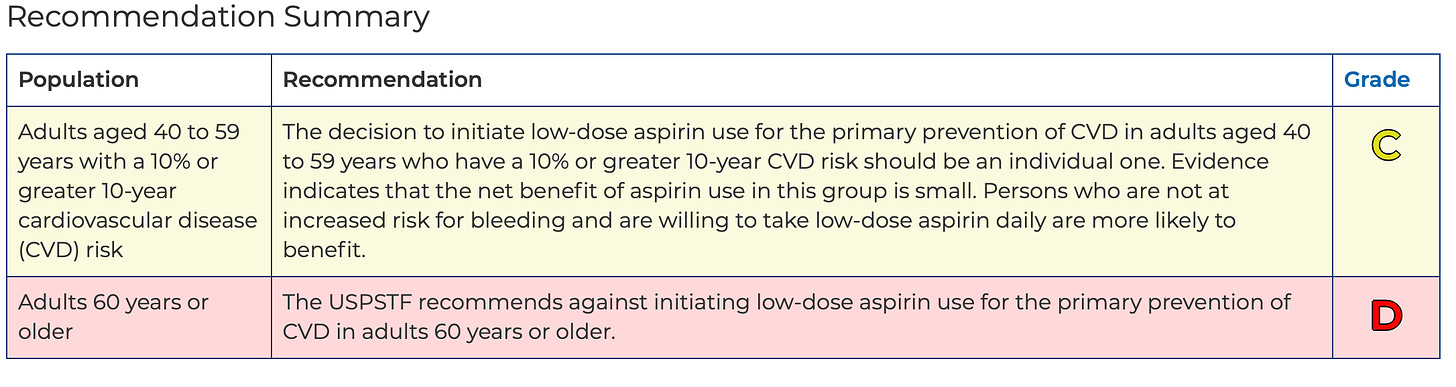

Following these trials, the US Prevention Services Task Forces modified their recommendations on who should be considered for aspirin therapy in the primary prevention setting6.

The main takeaway was that those aged 40 to 59 at higher risk should be considered for aspirin therapy on an individualised basis, and those aged 60 or older should not receive aspirin therapy for primary prevention.

These recommendations were based primarily on the three studies mentioned above, but a major criticism of these studies was that the rates of heart attacks etc., was very low, in the order of 1% and therefore, in such a low-risk group, it would be very unlikely that they would benefit from aspirin therapy.

The implication being that if a higher-risk group had been evaluated, that benefit would have been shown.

Treating Heart Disease Versus Risk

When it comes to secondary prevention, where we have much greater evidence of the benefit of aspirin therapy, the common link is that the patient has documented coronary artery disease.

So what if we looked for patients who had existing coronary artery disease and then assessed the benefits of aspirin therapy?

CAC or CT Coronary Artery Calcium scoring is a noninvasive imaging test that is used to assess for the presence of calcification in coronary arteries.

Calcification indicates the presence of coronary atherosclerosis, and a higher number indicates more plaque. A CT Calcium Score of 0 typically reflects a low probability of plaque in the coronary arteries and, by extension, a low risk of a heart attack over the following 5 to 10 years7.

On the basis of modelled data, so not a prospective randomised trial, the evidence suggests that those with more extensive coronary artery disease are likely to benefit from aspirin therapy8.

Importantly, for those with no advanced atherosclerosis and a CT CAC score of 0, the use of aspirin therapy was much more likely to cause harm rather than benefit.

The dashed red line in the graph above indicates the average number needed to harm over a 5-year period at 355. In simple terms, for every 355 people treated with aspirin therapy, one would be harmed by a major bleeding event.

For those with limited amounts of plaque or no plaque, as evidenced by a CAC score of 0 or less than 100, the net outcome suggested harm with aspirin therapy.

However, for those with a CAC score of >100, the net outcome suggested a benefit.

There was, of course, still a bleeding risk, but the risk of a heart attack etc. was much higher and therefore, on balance, they would be expected to fare better.

What Now?

In practice, what this means for patients is this:

-

If you have had a heart attack, stent or bypass, you almost certainly need to stay on your aspirin therapy. Do not stop taking it.

-

If you have not yet had an event and are on aspirin therapy, you should certainly have a discussion with your doctor to assess your expected net benefit. DO NOT STOP TAKING YOUR ASPIRIN WITHOUT CONSULTING WITH YOUR DOCTOR.

The decision to use aspirin therapy for the prevention of a first heart attack requires a lot more careful consideration than it once did.

It does, however, illustrate that we must always continue to re-evaluate the net benefit of the treatments we prescribe, particularly when they come with potentially significant downsides.

As always, this is a game of odds.

We must always try to inform ourselves as much as possible of those odds and then bet accordingly.

But as ever, it is just a bet.

Aspirin for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Time for a Platelet-Guided Approach. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022 Oct;42(10):1207-1216.

Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women and men: a sex-specific meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.JAMA. 2006; 295:306–313.

Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, Cricelli C, Darius H, Gorelick PB, Howard G, Pearson TA, Rothwell PM, Ruilope LM, Tendera M, Tognoni G; ARRIVE Executive Committee. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018 Sep 22;392(10152):1036-1046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31924-X. Epub 2018 Aug 26. PMID: 30158069; PMCID: PMC7255888.

Effects of Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Persons with Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18;379(16):1529-1539.

ASPREE Investigator Group. Effect of Aspirin on All-Cause Mortality in the Healthy Elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18;379(16):1519-1528.

https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-preventive-medication

Impact of Statins on Cardiovascular Outcomes Following Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Dec 25;72(25):3233-3242.

Coronary Artery Calcium for Personalized Allocation of Aspirin in Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in 2019. Circulation. 2020;141:1541–1553