How To Estimate Your 'Real' Risk Of Heart Disease

Assessing your risk of heart disease is no secret.

The devil is in the detail, though.

The problem is doctors use different models, and the model used can provide very different estimates of risk.

It’s not that one model tends to be right and the other wrong; it’s mainly down to the time frame over which the model is assessing your risk.

You have heard these figures before, but they are worth repeating to emphasise the point of cardiovascular risk; why it’s important to assess and, more importantly, manage.

Globally, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death.

By almost a factor of two.

In developed nations, it is on par with the risk of death secondary to all cancers - combined.

For most people, the chance of dying from cardiovascular disease is about 35%1.

So we know what the chances of dying from cardiovascular disease are in general, but how do we get a better picture at an individual level?

This is where the risk model comes in.

Most guidelines suggest estimating the risk of a cardiovascular event, such as having a heart attack or a stroke, over a 10-year time frame.

I find this model somewhat useless, and my refrain is:

“A ten-year risk model is only useful for someone planning on living another 10 years”.

This 10-year risk estimate is likely what you get when you attend your doctor.

They use this model because the guidelines tell them to use it. Not because they are purposefully misleading you.

Let's see how it works and why it has some serious limitations.

First off, this applies to all the models we will mention. They estimate the chances of an event in a population with a set of risk factors. I.e. out of 100 people with these risk factors, 7 will have a heart attack over the next 10 years.

However, you don't know whether ‘you’ will be one of those 7 people.

There is no way of knowing this.

But you still have to act and try to tilt the odds as much as possible in your favour.

Remember, this is all a game of odds.

Risk Calculators

The most commonly used 10-year risk calculators are the QRisk and ACC/AHA risk calculators. There are many others, but these are the most commonly used.

It is important to note that these calculators are only used in those who do not already have heart disease.

If you already have heart disease, you are at high risk.

The inputs to these calculators vary, but in general, the inputs include:

-

Age

-

Sex

-

Ethnicity

-

Smoking Status

-

Diabetes status

-

Family History of early heart disease

-

Blood Pressure

-

Cholesterol levels

-

BMI

Let’s take a hypothetical overweight 40-year-old white female with an early family history of heart disease, moderately elevated blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Before we use the calculator, I want to use a different risk estimation technique; the ‘Ask Your Aunty’ method.

If you asked your Aunty was the above person at high risk of heart disease in the future, what would she say?

She would say yes. She would!

Let’s see what the calculator says when we input the patient’s figures.

It says the above patient is ‘Low risk'.

This translates to a 1.3% chance of a cardiovascular event over the next 10 years2.

The recommendation is lifestyle change (Of course) and no indication for any medications.

It looks like your ‘crazy aunty’ was wrong on this occasion.

Now I would like you to take out your ‘Bullsh!t Detector’ and ask yourself if the calculator is wrong and your ‘Crazy Aunty’ was right.

Of course, your crazy aunty is right.

The reason for the discrepancy is the factor of time.

Over the next 10 years, the model is correct that this individual has a low risk of a cardiovascular event, i.e. a stroke or a heart attack.

But over the next 20, 30, 40, 50 years, the risk is way higher than it should be, and this is why your ‘Crazy Aunty’ is correct.

This multi-decade time frame is what we are interested in, not the next 10 years.

So let’s use a different calculator for the same individual.

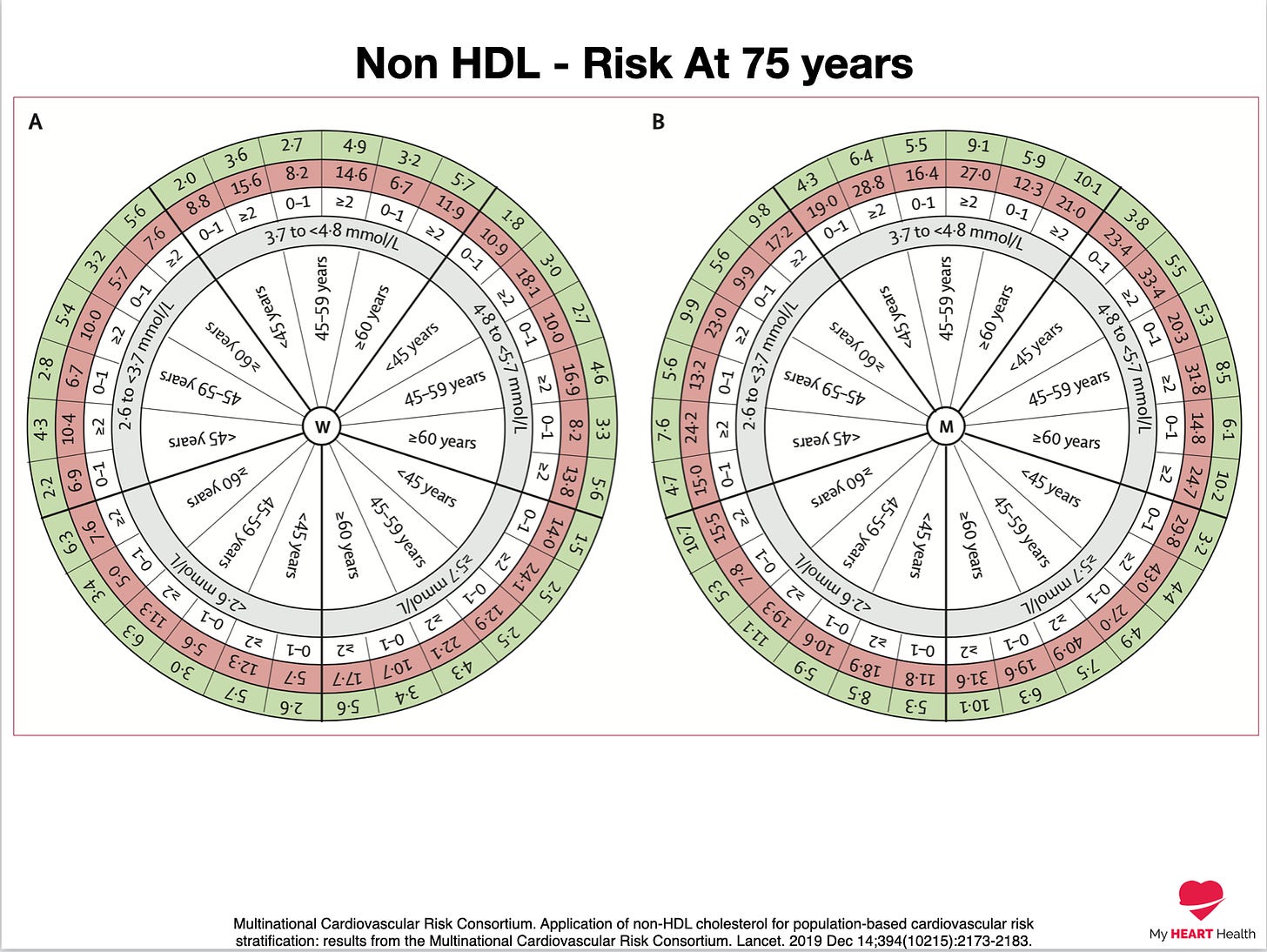

One that calculates the risk of a heart attack or stroke by age 75, which is 5 to 10 years short of the average female life expectancy in a developed nation3.

Using the patient’s age, sex, cholesterol and weight, we can estimate the risk of a heart attack or stroke by age 75 years of age is 18%. That's an almost 1 in 5 chance. This risk can be reduced to 3% if the patient’s cholesterol is reduced by 50%4.

To do so would typically require medications.

Not looking so ‘Low Risk’ now.

And it seems that medications, in addition to aggressive lifestyle changes, might be necessary.

But things are about to get a whole lot worse.

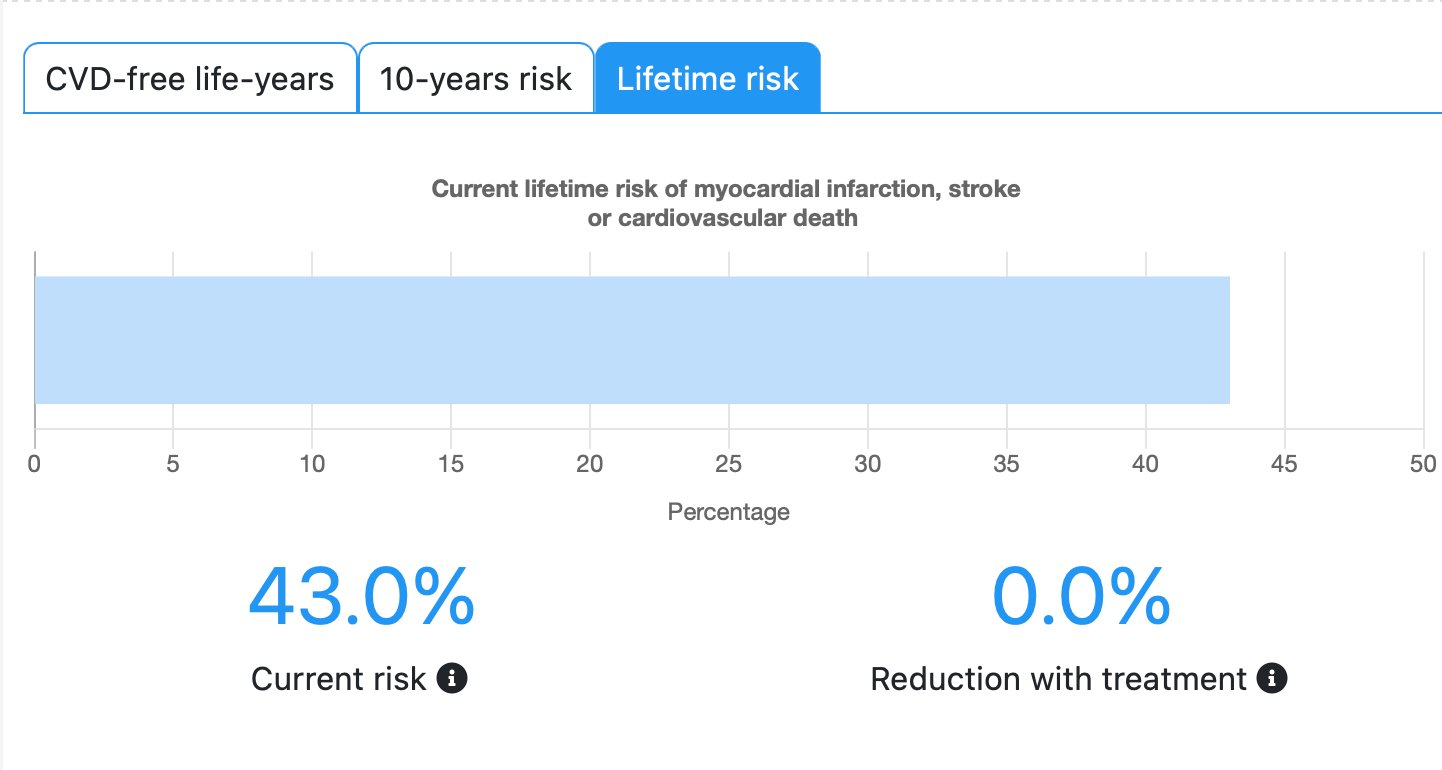

Let’s look at this patient’s lifetime cardiovascular risk.

That is the chances of having a heart attack, stroke or dying from cardiovascular disease over their entire lifetime.

With the above patients’ risk factors, their lifetime cardiovascular risk is now 43%. Remember, the average risk is about 35%.

Your ‘crazy aunty’ was spot on.

As was your ‘Bullsh!t Detector’.

This patient has ‘High Risk’ written all over them.

But just not in the next 10 years.

Which is the time frame over which most calculators estimate risk. Hence the ‘Low Risk’ result we got at the start.

This ‘Low Risk’ figure is the result you are likely to get from your doctor when you ask them to estimate your cardiovascular risk.

See the problem.

Let’s also calculate the benefits of getting blood pressure and cholesterol to target.

With medications, a 20% absolute risk reduction is possible, which is effectively cutting the risk in half.

But that’s WITH treatment.

If the same 40-year-old female were to be of normal weight, with normal blood pressure and cholesterol, their lifetime cardiovascular risk would be only 8%.

This is, of course, if they did not need treatment in the first place and they got there by way of excellent lifestyle behaviours and likely a touch of genetic good fortune.

Assessing cardiovascular risk is no secret.

But now you know its limitations.

Always remember that the risk of cardiovascular disease applies over a lifetime.

Not just the next 10 years.

Have you been told you are ‘Low Risk’?

Are you sure?

https://ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death

https://tools.acc.org/ascvd-risk-estimator-plus/#!/calculate/advice/riskgraph/

https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy

Multinational Cardiovascular Risk Consortium. Application of non-HDL cholesterol for population-based cardiovascular risk stratification: results from the Multinational Cardiovascular Risk Consortium. Lancet. 2019 Dec 14;394(10215):2173-2183.