Revolutionary Results: How Modern Obesity Medications are Changing the Game

I don’t usually quote Vladimir Lenin, but he may have had a point when it comes to weight loss medications.

"There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen"

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

That’s what the field of obesity therapeutics feels like right now.

Historically, weight loss medications have been a graveyard of failures.

Everything changed with the introduction of the GLP1 agonist, Semaglutide, which you likely know as Ozempic.

I have written about GLP1 and GIP medications previously here.

Since then, a LOT has changed.

Let's look at some of the recent advancements in this field.

What is new, and where are we starting to see some cracks in the weight loss medication drug class?

First, there was Semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy) and Tirzepatide (Mounjaro), showing reductions in weight of 15 to 20%.

The results were nothing short of astounding.

No drug option had even come remotely close to these reductions in weight.

They were so successful that annual sales for Tirzepatide alone are expected to exceed $50 billion1.

Many pharmacies ran out of stock, and access was often restricted to keep available supplies for diabetics where the drug class had originally been developed.

As a result of such meteoric sales, the manufacturer of semaglutide, Novo Nordisk’s market capitalisation exceeded the GDP of its home country, Denmark2.

Such levels of sales are not normal.

But this medication class continues to explode.

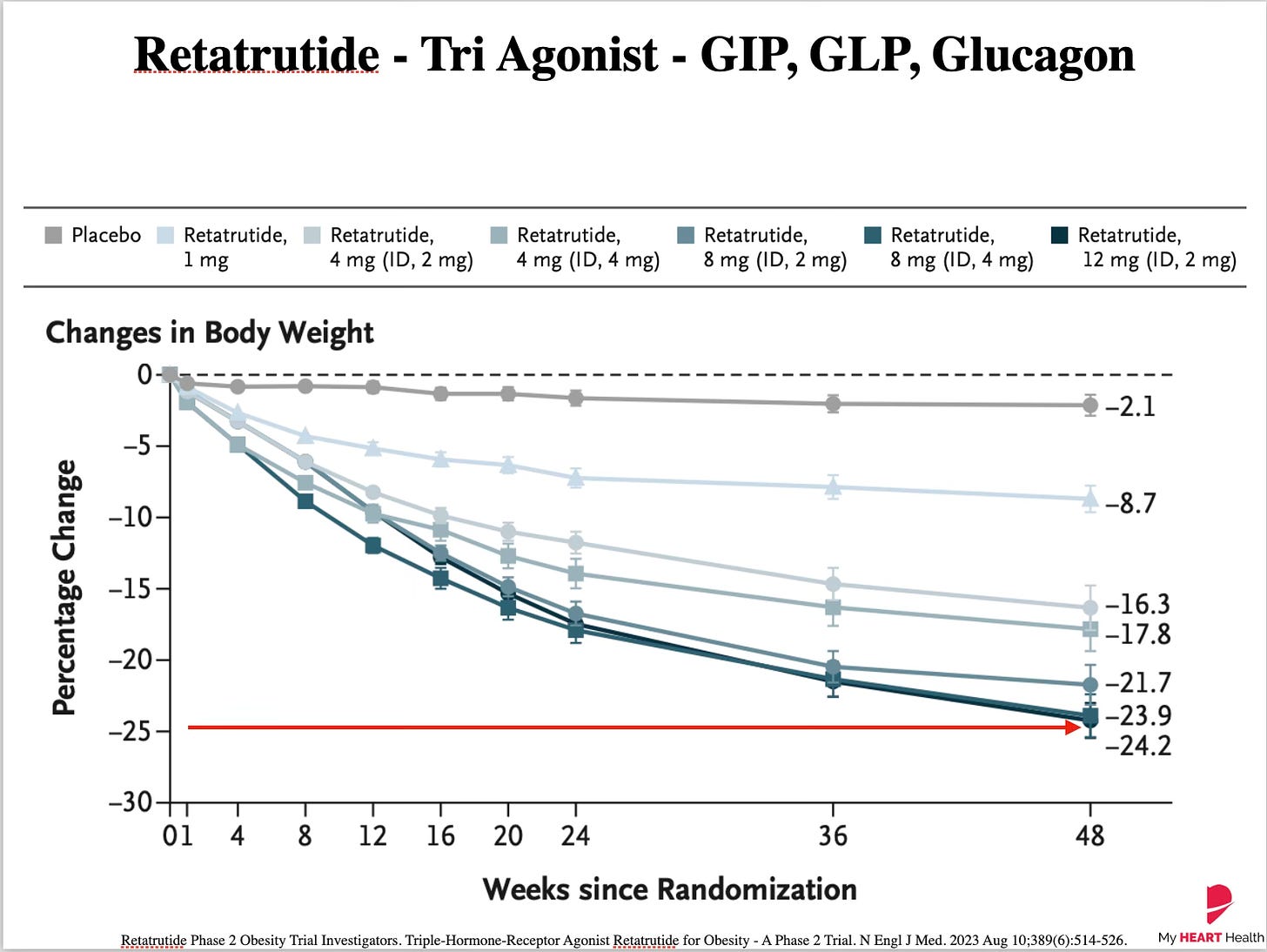

In addition to the GLP1 and GIP drug classes, there are now triple therapy combinations that also modulate glucagon.

These therapies have demonstrated even more impressive reductions in weight, with many patients losing 24% of their body weight in less than one year3

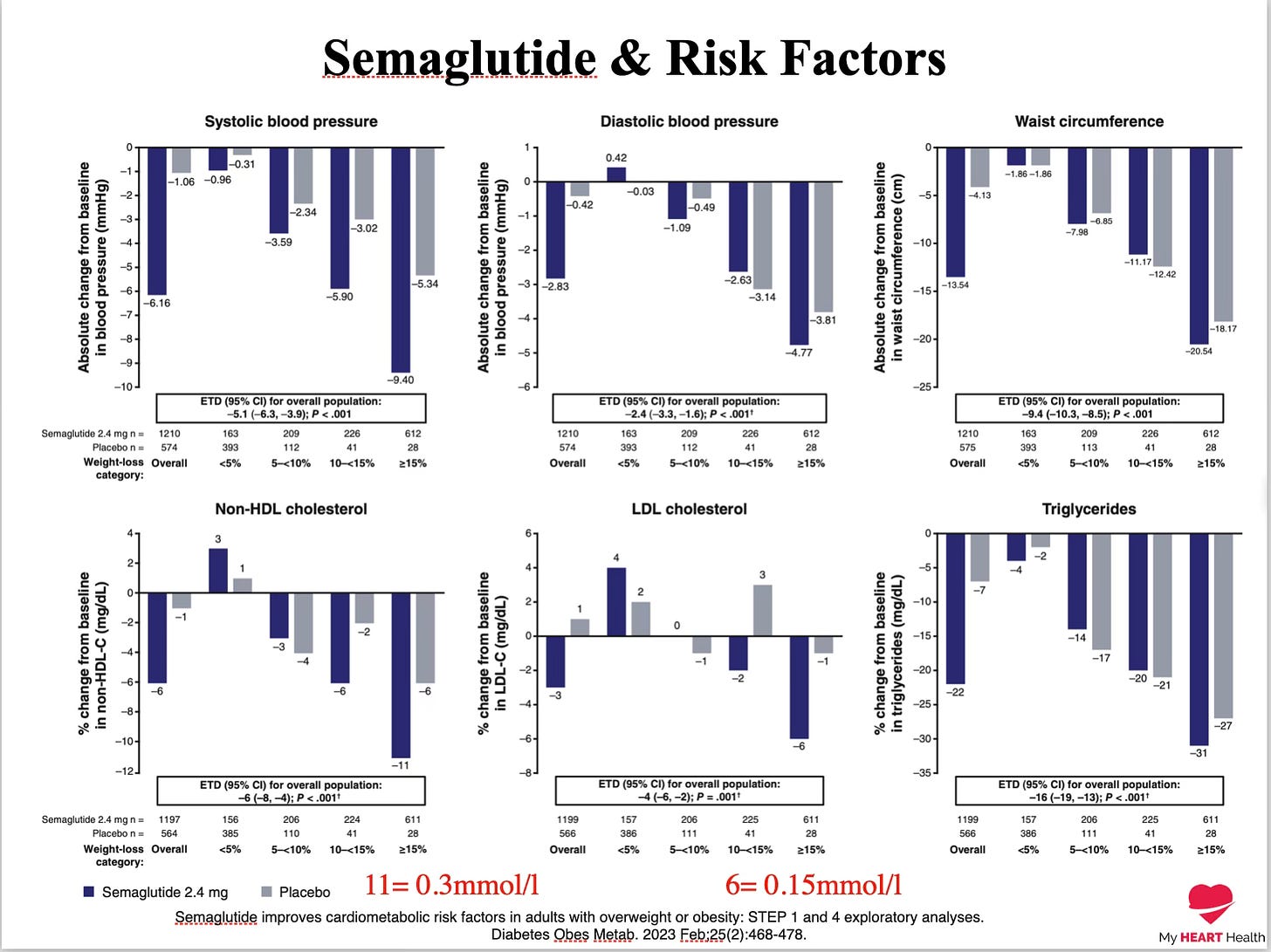

But it’s not just weight that improves.

In addition to reductions in weight, multiple risk parameters, including blood pressure, waist circumference and lipids, also improve.

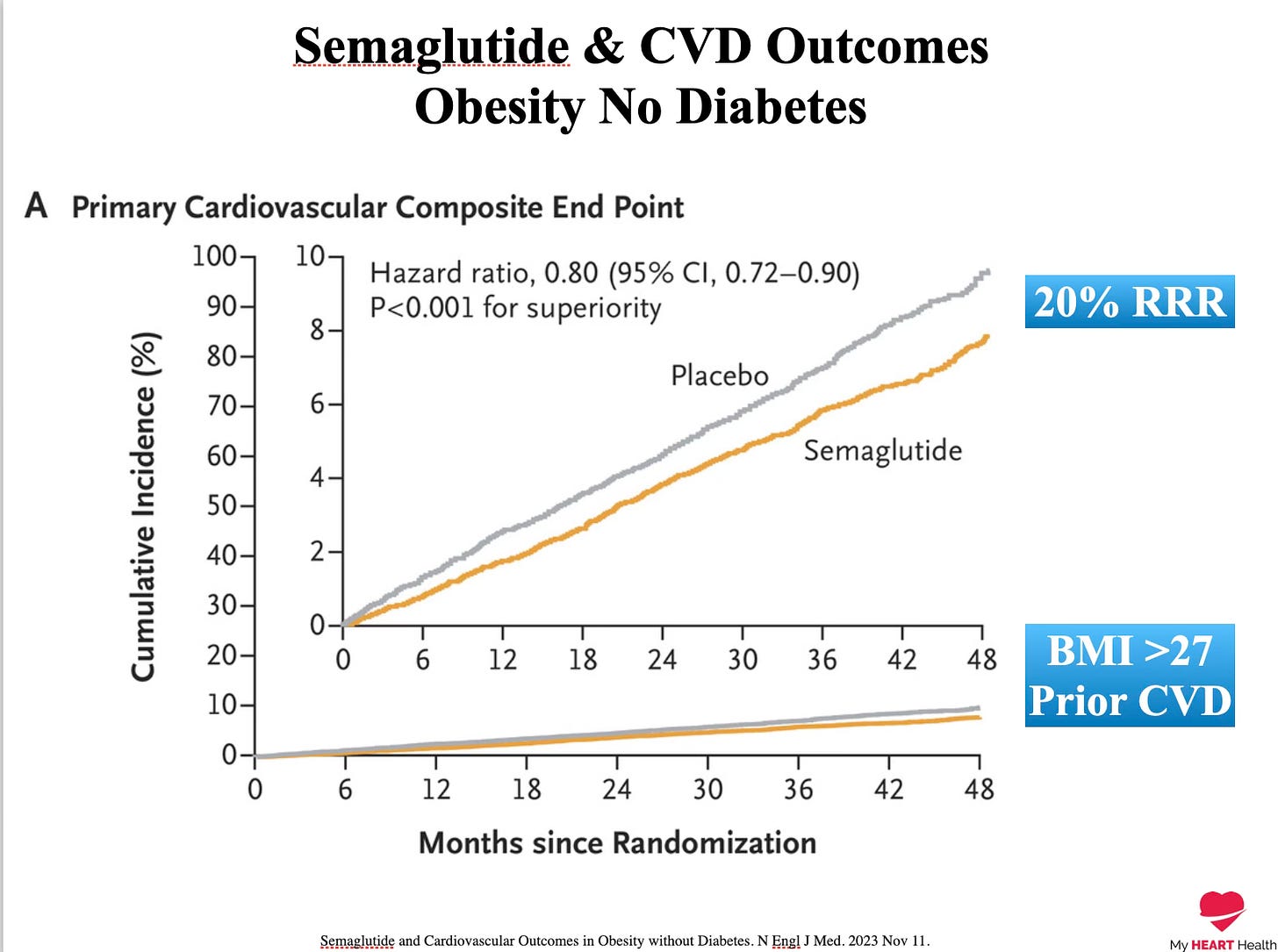

The primary reason for managing risk factors is to reduce events, including heart attacks.

Recent data has shown that these medications also reduce the incidence of major heart events by 20%, including heart attacks and cardiovascular death and also extend lifespan in those with a prior heart attack4.

The SELECT trial is currently underway to assess whether major heart events are reduced using Semaglutide in those without a previous heart attack5.

There is even emerging evidence that the use of such therapies may even reduce the risk of colorectal cancer by up to 50%6.

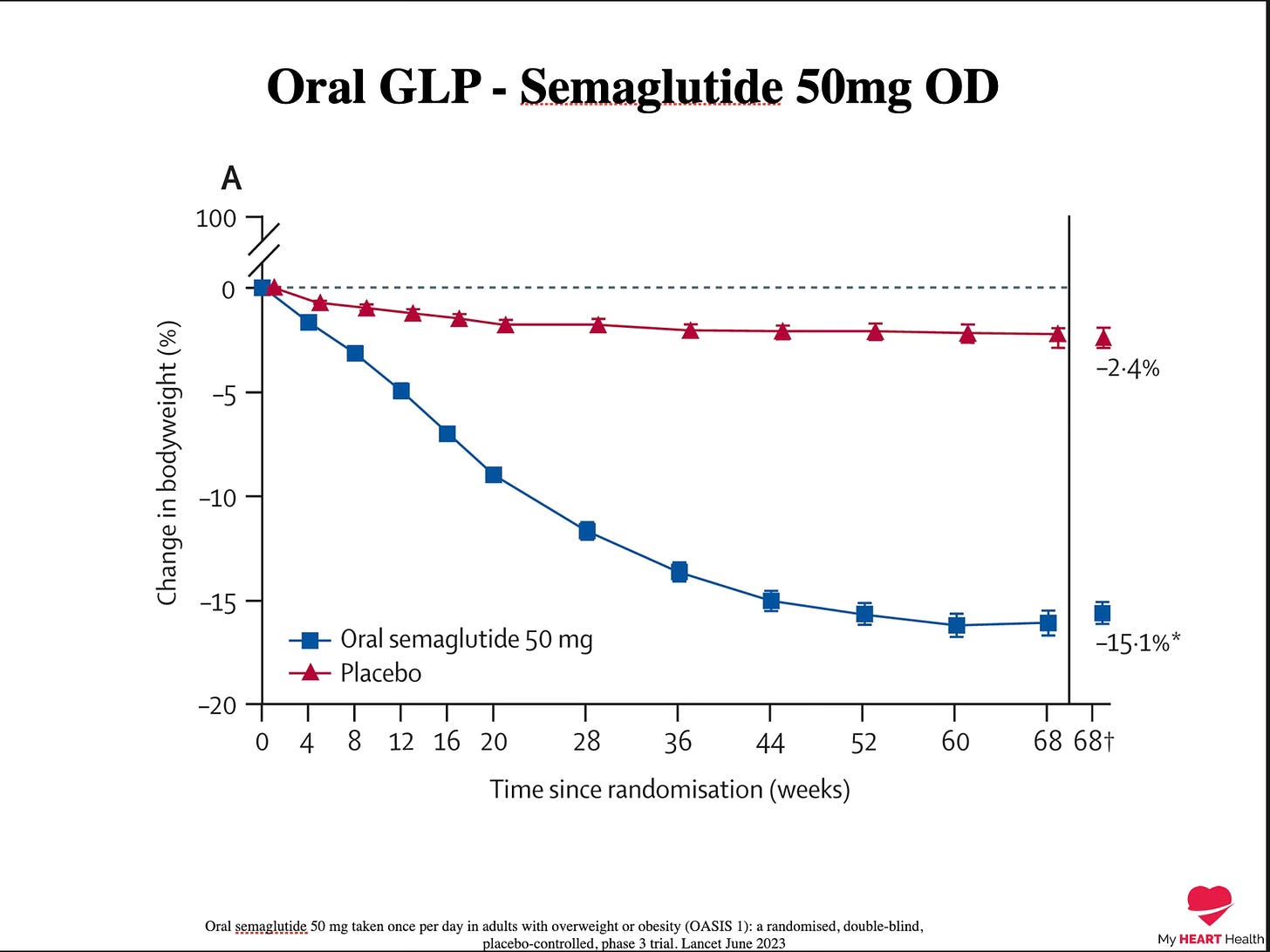

Will These Therapies Always Be Injectables?

One drawback to these therapies has been they are given in an injectable form, usually once per week.

Oral formulations of Semaglutide have shown promising results with reductions in weight of 15% achieved7.

But what about the downsides?

As with any therapy, there are always potential downsides.

One of the biggest criticisms has been that weight loss medications are actually making people ‘fatter’!

How is that possible?

All of the studies to date have focused primarily on total body weight loss, but that total is made up of both fat mass and lean mass, which is mainly muscle.

Low levels of muscle mass are associated with a range of adverse outcomes, and a therapy that causes this would not be a good long-term health strategy.

If more lean mass than fat mass is lost, although a person’s body weight may have dropped, their body fat percentage may have actually increased.

Hence, they have gotten ‘fatter’.

Let’s look at what the data says.

First, we must acknowledge that with any weight loss approach, fat mass and lean mass will likely reduce.

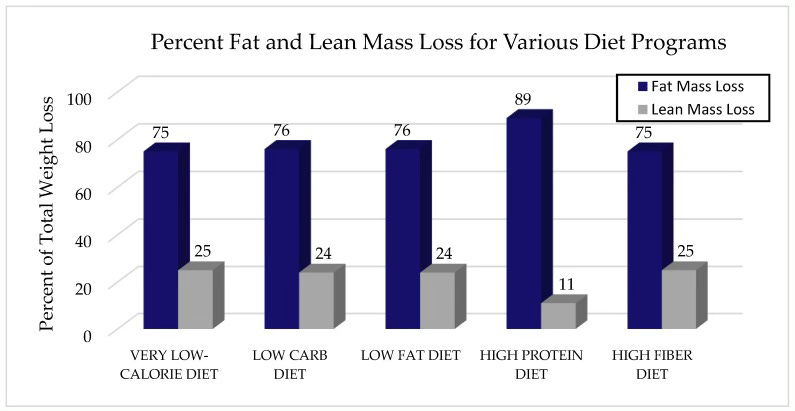

What seems clear, however, is that a higher protein diet minimises the degree of lean mass loss8.

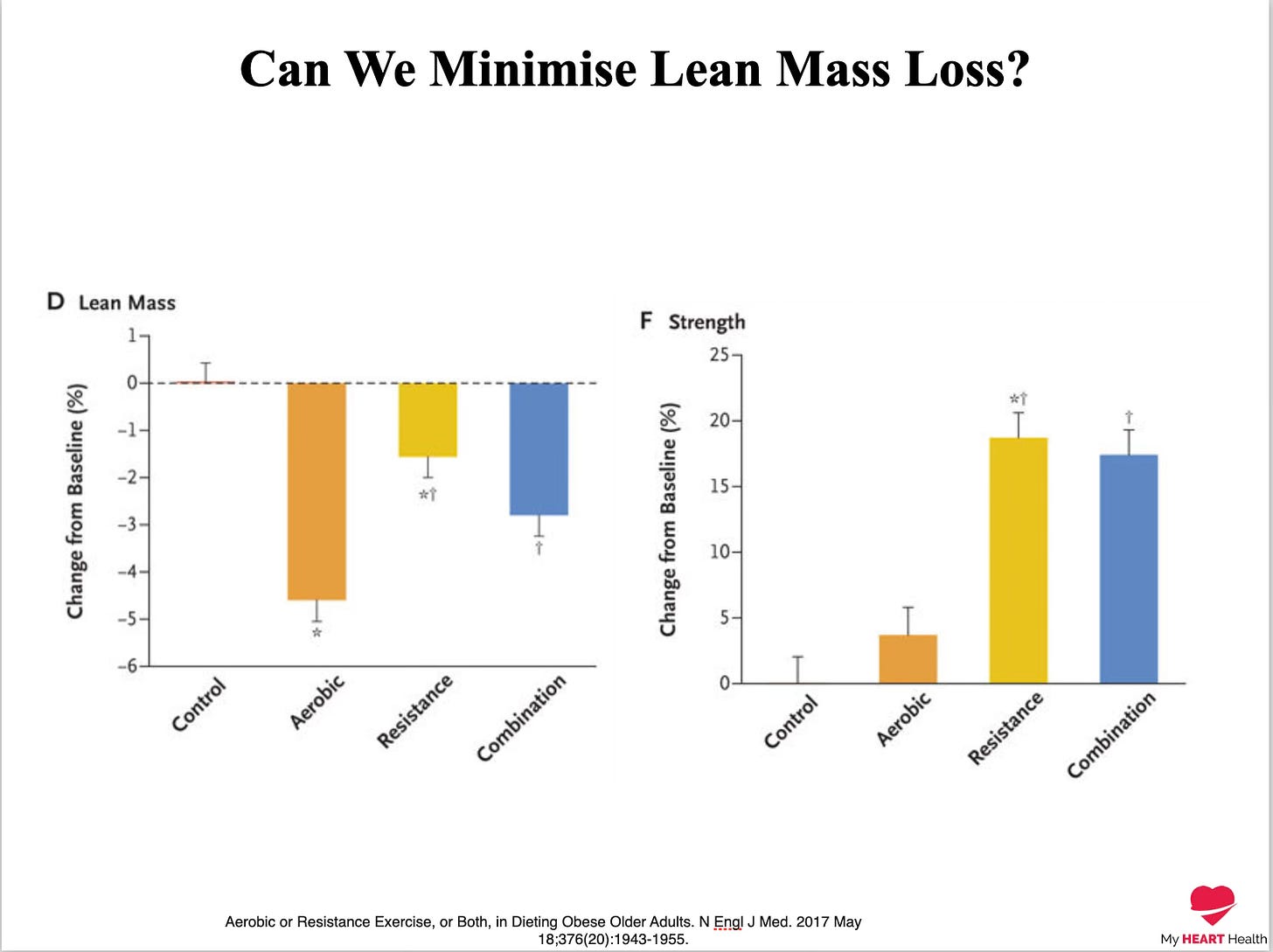

Secondly, during a dieting phase with a resultant weight loss of 9% of body weight, resistance training or combining resistance and aerobic training leads to the least amount of lean muscle mass loss9.

Let’s see what happens when weight loss medications are used.

A smaller sub-study of the original semaglutide trial looked at this very issue using body composition analysis using DEXA scans.

On average, these patients lost 13.6 kg of total body weight, but 5.26 kg was lean mass, accounting for 38% of the lost weight.

This 38% figure is an average.

In my experience, some patients lose substantially more lean mass as a percentage.

However, the ones who lose the least lean mass tend to have two things in common.

-

They eat a high-protein diet.

-

They continue resistance training throughout treatment.

Precisely what the literature tells us is likely to lessen muscle mass loss.

Rare Complications Are Not Rare At Scale

A small percentage of a very big number is still a pretty big number.

Adverse events occurring at less than 1% frequency occur at a relatively large absolute level when very large numbers are treated.

With these new therapies, we are increasingly seeing patients with10:

-

Pancreatitis

-

Bowel obstruction

-

Gastroparesis

I want to emphasise that these side effects are rare, but we will see them more often with such widespread use.

Weight Loss Medications Are Tools, Not Magic Tricks.

As with any new invention, we need to see it as a tool rather than a panacea.

Undoubtedly, if weight reduction can be achieved using lifestyle measures alone, that would be the preferable outcome.

However, many patients will need the additional support of drug therapy to get them to target.

This is no different to how we manage high LDL cholesterol or high blood pressure.

Additionally, for those who use these medications for weight loss, all efforts must be made to minimise muscle mass loss.

But we must also recognise that some muscle mass loss is likely.

As Thomas Sowell once famously said:

“There are no solutions, only trade offs”.

The pace of change in this field has been incredible.

What was once an area of healthcare that had few reliable interventions, this drug class has revolutionised the management of excess weight and obesity.

But like all new fields, we continue to discover pitfalls along the way and how best to navigate them.

We are in a new era of care that seems only just to be beginning.

https://fortune.com/2023/04/27/powerful-new-obesity-drug-tirzepatide-eli-lilly-expected-best-selling-drugs-all-time-sales-over-50bn-year/

https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/news/novo-nordisk-market-cap-higher-than-danish-gdp-obesity-drugs/?cf-view

Retatrutide Phase 2 Obesity Trial Investigators. Triple-Hormone-Receptor Agonist Retatrutide for Obesity - A Phase 2 Trial. N Engl J Med. 2023 Aug 10;389(6):514-526.

SELECT Trial Investigators. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023 Nov 11.

Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People With Overweight or Obesity (SELECT) rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2020 Nov;229:61-69.

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Drug-Naive Patients With Type 2 Diabetes, With and Without Overweight/Obesity. JAMA Oncol. Published online December 07, 2023.

OASIS 1 Investigators. Oral semaglutide 50 mg taken once per day in adults with overweight or obesity (OASIS 1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023 Aug 26;402(10403):705-719.

Body Composition Changes in Weight Loss: Strategies and Supplementation for Maintaining Lean Body Mass, a Brief Review. Nutrients. 2018 Dec 3;10(12):1876.

Villareal DT, Aguirre L, Gurney AB, et al. Aerobic or Resistance Exercise, or Both, in Dieting Obese Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20):1943-1955. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1616338

GLP-1 agonists linked to adverse gastrointestinal events in weight loss patients BMJ 2023; 383 :p2330 doi:10.1136/bmj.p2330